Warlord Games

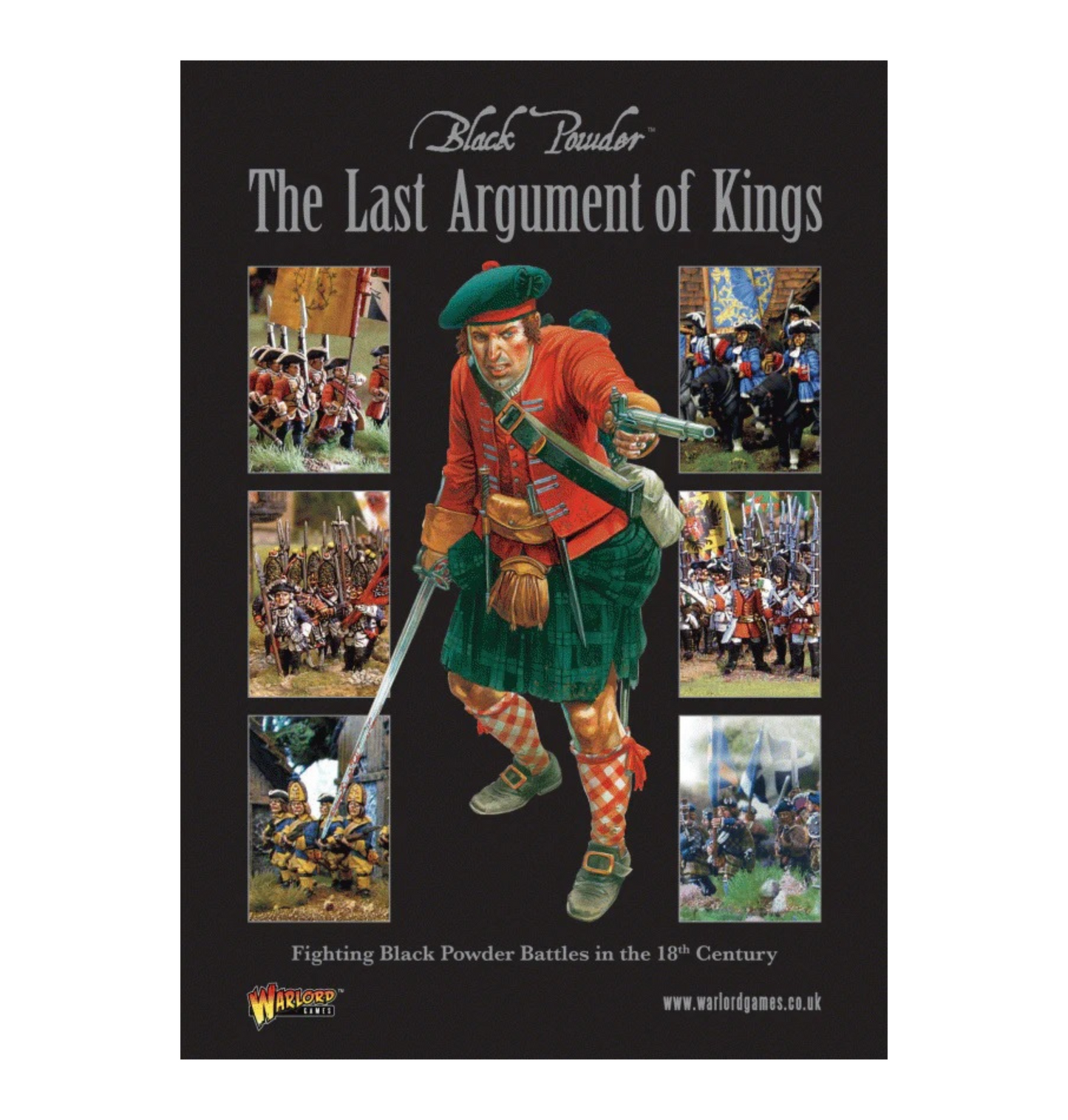

Black Powder The Last Argument of Kings

Couldn't load pickup availability

Disclaimer: This is not a physical product. You will receive a digital download of your eBook after your purchase.

The beginning of the eighteenth century saw a huge change in how wars were fought. The first and most dramatic development was the universal use of the musket by professional European armies. This change in weaponry demanded a complete rethink of the tactics employed on the battlefield by all three arms of infantry, cavalry and artillery. This was an age of experimentation, when new ideas could lead to sweeping victory or crushing defeat. By the time of the Seven Years’ War, in the middle of the century, the practice of linear tactics had reached their zenith, with practically all European armies organising and training along similar lines to an agreed set of principles.

This chapter provides a general introduction to early eighteenth century armies, how they fought and how they were led. It is not intended to be exhaustive, but rather to be a gentle introduction and also to rationalise some of the special rules you will see later in this book that will give this period its unique flavour. As you will see, this is an age of poor command, ponderous manoeuvre, pistol-firing cavalry and ineffective artillery. Anyone approaching these battles as ‘Napoleonics with tricornes’ will quickly come a cropper.

Generals and Command

In these days of professional army officers and generals it seems strange to us that in the eighteenth century the lives of thousands of men could be placed in the hands of a complete buffoon. Such was often the case, however. High rank in all European armies owed more to birth and social standing than to competence or ability. The British army retained its tradition of selling commissions until the end of the century, whilst in the French army certain youths of noble birth were given rank automatically because of who they were. Duffy notes that “the young men from powerful court families could reasonably expect to become subalterns at around fifteen, captains at eighteen and colonels at twenty-three.”

Marshal Saxe had to put up with many such generals: “Because of their high birth, the princes of the blood automatically claimed the high rank of lieutenant general…the incapacity of four of them was general knowledge.” The Comte de Clermont was so incompetent that Louis XV forbade him from giving any orders to the troops of his brigade, while the Comte d’Eu was not allowed to interfere with the deployment of the artillery that he commanded! Other armies were not well served either. The Dutch general, Schlippenbach, says of his colleagues that “Of the four major generals commanding the Dutch cavalry, one was so old he could hardly sit a horse, a second was of such unwieldy proportions that he gave his orders from the window of a berlin, another was such a hypochondriac that at times he was out of his mind, while the fourth was an invalid.”

Prussia was the first army to promote on ability, but even here Frederick liked all his officers to be from noble families. That said, this was the best army to get promoted within if your ability was greater than your lineage. However, this age also produced some of the greatest generals ever to command an army. Chief amongst them must be John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, who surely has a claim to being Britain’s best ever general. The age also produced Frederick of Prussia, Prince Eugene of Savoy, Marshal Maurice de Saxe… The list could go on and on.

The point is this: armies in the early eighteenth century were still semi-feudal, and command lay with those who were born to it or could afford to buy into it. Some of these commanders were exceptional and were capable of great things. Most did their best. Some were buffoons. Do not expect all of your miniature brigade commanders to perform well or do as they are told. You have been warned.

Raising & Training Your Regiment

So if you imagine you are a member of a noble house who has the funds and the necessary permission from the king to go about the raising of a regiment, how would you go about it? It is widely held that all the soldiers in the armies of the eighteenth century were the dregs of society, the “scum of the earth” as Wellington rather famously described them. It is often said that men were forced into service by the press-gangs or that the prisons were swept of undesirables who were put into uniform. Nothing could be further from the truth. In most armies, the troops were volunteers to a man. It is true that some volunteered due to hunger or unemployment – a life in the army offered them the only real alternative to death in poverty. However, for the average eighteenth century youth, the army offered three square meals a day, clothes on your back and a roof over your head, all of which, in those hard times, were far from certain in civilian life.

Share